Memory in Metal: The Enduring Power of Renaissance Portrait Medallions

By Dr. Mark Joseph O’Connell, Aug. 29, 2025.

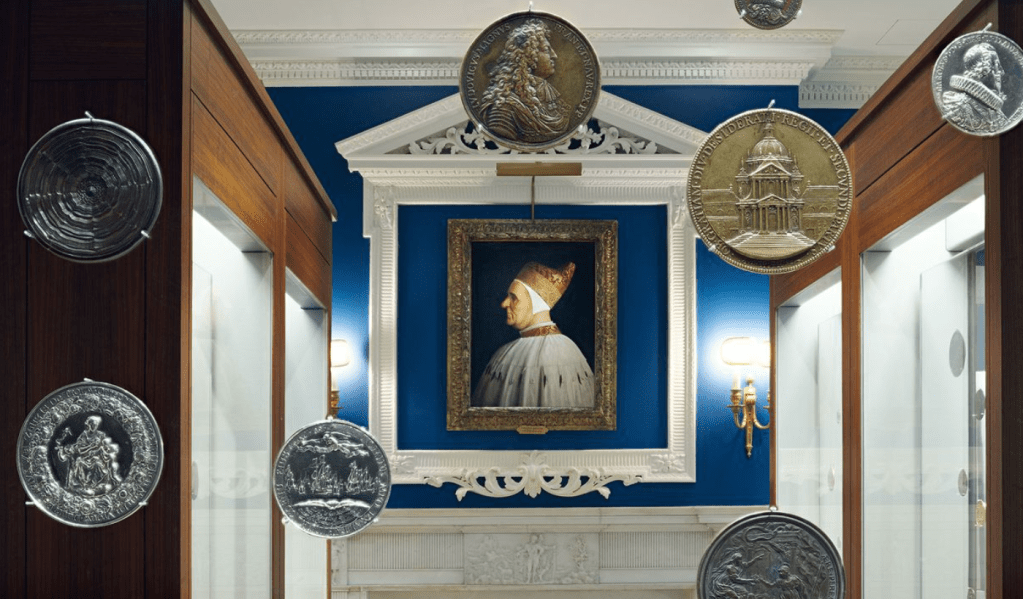

Fig. 1: The Medals Room, The Frick Museum, NYC. Image courtesy of The Frick Museum, NYC.

“This is not the face as mirror of the soul, but as sigil of the self.”

The Mnemonic Sigil Perdures: Italian Renaissance and Later Metal Medallion Portraits from the Frick Museum Collection O’Connell (2025)

Climbing the grand staircase, a feature once off-limits to the public (fig. 2), I felt the frisson of gaining entry into an architectural and aesthetic sanctum long withheld (and repurposed as offices no less). I am at the Frick, ever a sanctuary for aesthetic reflection, which has with this renovation reoriented its internal dialogue: what was once a hushed sequence of ground-level rooms, heavy with Rembrandt, Bellini, and Ingres, now opens upward (literally and metaphorically) into an expanse where history and intimacy converge. A brief architectural note is warranted here. Originally the 1914 Carrère and Hastings mansion on 5th Avenue of Henry Clay Frick, the building was bequeathed with the explicit condition that its domestic scale be preserved, even as it morphed into a public institution. The long-anticipated renovation, overseen by Selldorf Architects, adheres to that spirit (Frick Museum n.p., n.d.), rather than disrupt, it restores.

The transformation of a space can do more than alter physical perception, it can resituate time, memory, and discovery. Such was my experience at the newly renovated Frick Collection in New York City, where the museum’s recent unveiling of its second floor not only altered my relationship to the building itself, but ushered in a deeper historical encounter, one I had not anticipated, and one that profoundly reshaped my scholarly attention. Light now fills what were once sealed corridors. Paintings long in storage or shown elsewhere are placed anew. But it was not the paintings that captured me that day. It was what I discovered in a quiet, nearly tucked-away second-floor room: the gallery of portrait medallions. Here, in the heart of this newly accessible space, lay a collection I had hitherto overlooked, rows of small, round metal portraits, glinting softly under discreet lighting. They seemed at first curious anomalies: miniature likenesses of forgotten princes, artists, physicians, noblewomen. But within moments, I understood their gravity. These medallions, some struck, others cast, many of them dating to the Renaissance and Baroque periods, pulled me into a different kind of portraiture. Not grand and painted, but intimate, compressed, and sculptural. Not devotional per se, but definitely commemorative. They bore the stylized facial profiles we associate with ancient coins or military medals, yet their intention was far more complex.When visitors ascend the newly opened second floor of The Frick Collection in New York, they are greeted not just by light-filled rooms and reopened galleries, but by a quiet chamber of unexpected resonance. Here, softly illuminated in glass vitrines, sit rows of small metal disks: portrait medallions. Bronze, silver, parcel-gilt, objects that might first appear modest in scale, antique in style, even obscure in function. But take a closer look, and something extraordinary emerges.

These medallions, many cast during the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods, aren’t just miniature portraits. They are compressed sculptures, coins that are not coins, artworks that speak with the authority of monument and the intimacy of touch. They carry the faces of dukes, artists, noblewomen, and scholars, rendered in profile and often paired with allegorical symbols or Latin inscriptions. Their purpose? To remember, signify, and to circulate identity across courts, across time, and in a very real sense, to perdure.

The Renaissance Medallion: Between Portrait and Propaganda

The Renaissance portrait medallion was born out of a moment of convergence. Humanist fascination with antiquity, the rediscovery of Roman coinage, and a renewed interest in individual identity all came together in 15th-century Italy. These weren’t coins for commerce. They were tokens of commemoration, of virtue, of self-fashioning.

The artist most often credited with inventing the genre is Pisanello (Antonio di Puccio Pisano), who in the 1430s created a cast bronze medal of the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaeologus. On one side, the emperor’s profile. On the other, a scene of him on horseback. It was a radical act: combining classical format with contemporary likeness, turning the individual into icon.

Soon, portrait medallions flourished across the courts of Ferrara, Mantua, and Florence. They were exchanged as diplomatic gifts, worn on chains, kept in cabinets of curiosity, and even placed in tombs. They were statements of lineage, of reputation, and of personal myth.

The Face as Sigil

Unlike the painted portrait, which often seeks to reveal emotion or psyche, the medallion compresses identity into a stylized, classical format. It shows the subject in profile, often accompanied by a Latin inscription and symbolic reverse. This is the self not reflected, but constructed; selected, idealized, and set in metal.

What makes the medallion remarkable is that within this reduction, individuality is still powerfully present. The slight tilt of a chin, the arrangement of curls, the line of a nose, all distinguish one sitter from another. But more than portraiture, this is branding avant la lettre. It is the public face as political emblem. A small sculpture designed not just to represent, but to circulate.

Metallurgy and Memory

“To sculpt a living body in metal is to translate the most perishable of substances: flesh, into one of the most enduring.”

The Mnemonic Sigil Perdures: Italian Renaissance and Later Metal Medallion Portraits from the Frick Museum Collection O’Connell (2025)

Casting or striking a likeness into metal was not simply an artistic choice. It was an ontological statement. Bronze does not fade like parchment. Silver resists rot. In a world rocked by plague, war, and upheaval, to be immortalized in alloy was to stake a claim on continuity.

To hold a medallion is to feel the literal weight of memory. As one moves between the obverse (the face) and the reverse (the narrative), one performs an act of interpretation. These disks are mnemonic devices, encoded with allegory, history, and aspiration.

Take the portrait medallion of Francesco Redi, created by the Baroque medalist Massimiliano Soldani. On one side: Redi’s lifelike face. On the reverse: a bacchanalian scene referencing his poem Bacco in Toscana, with the inscription CANEBAM: “I sang.” Centuries later, the medal still echoes that claim to intellectual vitality.

Fig. 2: “Francesco Redi”(Recto) Medalist: Massimiliano Soldani (Italian, Montevarchi 1656–1740 Montevarchi) (1684). Italian, Florence. Metropolitan Museum: Object Number: 1986.19.

Fig. 3: “Francesco Redi”(Verso) Medalist: Massimiliano Soldani (Italian, Montevarchi 1656–1740 Montevarchi) (1684). Italian, Florence. Metropolitan Museum: Object Number: 1986.19.

From Courts to Empire: The Medallion Evolves

As the medallion form spread across Europe, it retained its Renaissance roots while adapting to new political contexts. In France, the neoclassical portrait of Joséphine Bonaparte, created by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers around 1804, fused classical imagery with Napoleonic ideology. Joséphine appears in elegant profile, adorned with pearls and a diadem, simultaneously an empress and a Roman matron. The medal doesn’t just commemorate her; it legitimizes a regime.

Fig. 4: Pierre-Jean David d’Angers (1788–1856), Empress Josephine Lapagerie Bonaparte, ca. 1804. Gilt bronze. Fricke Museum, NYC, from the Stephen K. and Janie Woo Scher Collection.

What unites these medallions across centuries is their dual function: personal relics and public instruments. They are intimate in scale but expansive in implication. A prince’s image circulated in metal could reinforce alliances, intimidate rivals, or secure dynastic legacy. A humanist’s likeness could establish scholarly authority. For women like Isabella d’Este, whose medals were crafted and collected with care, the medallion became a powerful tool of courtly and cultural self-assertion.

Circulation as Power

Unlike frescoes or oil portraits bound to palaces or chapels, medallions moved. They were mobile sculptures, worn, traded, gifted. In their portability lay their potency. They crossed borders and centuries, leaving behind a trail of presence and influence.

At the Frick, this aspect is brought beautifully to life. The current installation of the Stephen K. and Janie Woo Scher Collection doesn’t present these medals as numismatic relics. Instead, they’re displayed as luminous jewels of cultural memory, miniature monuments whispering across time.

Fashioning Identity: Dress, Ornament, and the Zeitgeist in Medallic Portraiture

It was most apparent to me in the Joséphine Bonaparte medallion (due to the size of the medallion as well as Joséphine’s lasting legacy as a tastemaker and style icon) how important the role of fashion was in many of these medallion depictions. The portrait medallion is not only a record of physiognomy after all but also a carefully orchestrated display of fashion. In an era when visual representation was inseparable from the social codes of attire, the sculpted surface of a medal condensed not just the face but the full symbolic language of status, taste, and temporality. The fashions depicted upon these small disks, whether through hairstyle, jewelry, insignia, or the drape of fabric, do not merely embellish likeness; they inscribe the sitter within the zeitgeist of their age, echoing broader currents in visual and material culture.

In the earliest fifteenth-century portrait medals of Pisanello and his contemporaries, fashion was instrumental in connecting contemporary rulers to the dignity of antiquity. Leonello d’Este’s medals, for example, present him in profile with a short, cropped hairstyle he wears a high, elaborately patterned garment or tunic, possibly a brocade or damask with a raised collar (fig. 5). The surface detail suggests woven or embroidered decoration, emphasizing his refinement and courtly status rather than military authority. Notably, Leonello is not shown in armor or with lavish jewels. Instead, his attire reflects the humanist preference for classical sobriety and an intellectual mode of rulership, this resonates with who he was as a leader, one recognized principally for his sponsorship of the arts, literature, and culture a: “perfect embodiment of the model of prince and man of letters that all humanists dreamed of as patron and defender of the arts” (Gosman, Macdonald & Vanderjag 2005, 32) (fig. 7). The simplicity of his garment and the absence of elaborate ornament signal the Renaissance ideal of the ruler as stoic, virtuous, and classically grounded. His thoughtful countenance is the most significant aspect of the medallion. This was not a literal depiction of what Leonello wore in court, where sumptuous velvets, brocades, and jeweled caps were common, but rather a constructed iconography, selectively quoting antiquity to fashion a timeless, dignified image.

Fig. 5: Antonio di Puccio Pisano, called Pisanello (ca. 1395–ca. 1455), Leonello d’Este (reverse), ca. 1445. Bronze. Fricke Museum, NYC, from the Stephen K. and Janie Woo Scher Collection.

In contrast, other Renaissance patrons leaned into courtly display. The medallic portraits of Isabella d’Este show her with a finely articulated coiffure, studded with pearls and jewels (fig. 6). These details echo her documented love of fashion and her role as a tastemaker in Italian courts (Hall 2021). By embedding such sartorial elements into the medallion, Isabella staged herself simultaneously as classical muse and modern patron, blending the cultural capital of antiquity with the currency of fashionability. As Sierra Hall’s study demonstrates, Isabella’s medals transformed the feminine sphere of ornament into a tool of political negotiation: fashion was diplomacy, and the medal was its condensed stage.

Fig. 6: Portrait Medal of Isabella d’Este (1495-98), Gold with diamonds and enamel, diameter 7 cm Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Hair, arguably the most visible and mutable element of Renaissance and Baroque fashion, was frequently emphasized in medallic portraiture. Women appear with intricately braided crowns, jeweled nets, or flowing curls, each style reflecting both personal identity and contemporary ideals of beauty. Men, by contrast, often wore short, stylized cuts, recalling both antique models and the sober discipline of civic humanism. By the seventeenth century, however, hairstyles on medals had grown more elaborate, mirroring the Baroque cult of spectacle, such as those seen on Francesco Redi (fig. 5)whose voluminous locks cascading in curls, an aesthetic closely tied to the fashionable emergence of the perruque (full wig). These sculpted strands, though compressed into bronze or silver, captured the theatricality of the period and aligned the subject with the performative grandeur of the era. In this way, the hair on a medallion was not mere portrait detail but a visual shorthand for an era’s values: restraint in the Renaissance, theatricality in the Baroque.

Jewelry, necklaces, earrings, and diadems, are other crucial elements of medallic fashion. On women’s portraits, pearls frequently appear, signifying not only wealth but also chastity and dynastic continuity. Anne of Austria on the verso of the Louis XIII medallion (fig. 10) shows the splendid lacework on her raised collar and neckline, as well as a conspicuously large pearl drop earring. King William III and queen Mary II are depicted in regal finery and even the cushions on which their feet rest have jaunty tassels (fig. 11). In the medallion of Empress Joséphine Bonaparte, David d’Angers meticulously rendered her jeweled diadem and pearl-studded coiffure, aligning her with both Roman empresses as well as Marian iconography. Here, ornament became a theological as well as political language: the jewels spoke simultaneously of feminine virtue and imperial power. Male sitters were often distinguished by chains of office, collars of orders, or martial accoutrements. The inclusion of the Order of the Golden Fleece or the Collar of the Annunziata would instantly situate the sitter within a network of European aristocracy. On a small disk, such insignia condensed entire geographies of allegiance, visually tethering an individual to dynastic webs.

The fashion I observed in the medallions was not only about outward display but was also about staging the drama of mortality. Memento mori motifs, particularly popular in the seventeenth century, paired elegantly dressed portraits with reverses showing macabre skulls as in the >> portrait. The juxtaposition of rich attire against symbols of death spoke to a Baroque sensibility that entwined splendour with ephemerality. Fashion itself became a metaphor for life’s brevity: glittering, fragile, and destined to fade. This interplay between costume and mortality resonates with broader Baroque visual culture, from vanitas paintings to funeral effigies, where the tension between worldly adornment and eternal salvation was a central theme. The medallion, portable and tactile, carried this duality into the intimate realm of exchange and possession.

Conclusion: Memory in Metal, The Medallion as Cultural Mnemonic

In conclusion, across their long trajectory from the courts of fifteenth-century Italy to the neoclassical ateliers of the seventeenth century, portrait medallions present more than a mere stylistic lineage or artistic genre. They reveal a persistent cultural impulse: the desire to solidify identity in metal, to anchor reputation, virtue, and presence in an object at once intimate and permanent. As this article has traced, the medallion’s form was deeply classical, its message profoundly Renaissance, and its afterlife surprisingly modern. Medallions emerged within a moment when humanist interests converged with numismatic practices and sculptural invention. They drew on Roman precedents not just aesthetically but ideologically: where Roman coins projected imperial legitimacy, Renaissance medallions projected individual distinction. These small-scale relief portraits became tokens of private fame, artistic mastery, and dynastic continuity. They were commissioned, exchanged, worn, collected, and, above all, remembered.

Renaissance and later Italian medallion portraits demonstrate how a small object can convey large cultural and political messages. They fused humanist celebration of the individual with classical forms, functioning as portable monuments that asserted identity and reputation. Artists pushed the boundaries of relief sculpture and narrative, often signing their works to claim authorship and elevate medals to the status of fine art (Met 2016). Today these medals provide invaluable historical evidence, preserving the likenesses and aspirations of people who might otherwise remain unknown (Met 2016). From Pisanello’s first portrait medal (Jones 2011) to Soldani’s Baroque masterpieces, Italian medallions illustrate the enduring power of miniature sculpture to capture and disseminate memory.

What makes the medallion so potent as a visual and cultural form is its synthesis of sculptural likeness and symbolic resonance. The profile portrait, stylized, flattened, monumental in its reserve, compresses the sitter’s identity into an icon of idealized presence. It is not portraiture as emotional revelation, but as emblematic essence. This is likeness reconfigured as legacy. Medallions, however, do more than preserve appearances. They encode narratives. The obverse fixes identity: the reverse unfolds meaning. Allegorical reverses, ranging from personifications of virtues to complex cosmologies, offer viewers a semiotic puzzle, a mythographic footnote to the public face. In this sense, medallions operated not simply as images, but as mnemonic devices. They turned the act of looking into an act of remembering, and often, of interpretation.

Their metallic composition only deepens their mnemonic charge. Cast or struck in bronze, silver, or parcel-gilt alloys, these objects resist ephemerality. Unlike parchment or paint, metal promises endurance. A medallion, once created, enters the world not as a document but as a durable token of memory. The weight of its substance echoes the weight of the life it commemorates. Yet this same materiality also draws the medallion into the economy of exchange. Medals, like coins, circulate. They are gifted, traded, sold, even hoarded. In this way, the medallion transfigures personal likeness into cultural currency. A face becomes a form of symbolic capital. Whether exchanged between courts or worn as a pendant, it functions both as artifact and as agent, both record and performance.

This duality, commemoration and circulation, is what makes the medallion such a powerful artifact of visual culture. It occupies a liminal space between intimacy and publicity, between sculpture and signage. It is an image meant to be held, but also to be shown. It is portraiture rendered into persuasion. Like medals awarded for military service or civic valour, these objects also confer honour. But where modern medals recognize public acts, Renaissance medallions often celebrated private aspiration: a scholar’s intellect, a prince’s prudence, a patron’s cultivated identity. In doing so, they did not merely reflect achievement, they helped to construct it. Today, these medallions offer scholars not only technical marvels of relief casting and narrative ingenuity, but historical windows into how Renaissance and Baroque individuals imagined themselves and wished to be remembered. They illuminate a time when metal bore memory, and when the portrait was less a mirror than a medium of immortality. In an age saturated with images and prone to the disposability of digital likeness, the Renaissance medallion endures as a reminder of another mode of portraiture, one that carved permanence from impermanence, and transmuted identity into alloyed form. Whether admired in a vitrine at the Frick or studied through a loupe in a numismatic archive, the medallion remains what it always was: a miniature monument to memory, and a testament to the enduring human urge to preserve the self in form, in symbol, and in time.

Portrait medallions, in all their alloyed subtlety, offer more than documentary likeness, they offer a philosophy of selfhood rendered in metal. As this essay has traced, these small sculptural forms emerged not only from humanist curiosity or classical revival, but from a deeper existential impulse: the desire to forge identity beyond the frailties of the body and the finality of time. In the medallion, the human face is distilled into essence, stylized, profiled, and encircled by inscription. This is the self not captured in passing but crafted for permanence. It is a portrait, yes, but one governed less by emotion than by emblematic clarity. What we encounter is identity selected, abstracted, and asserted: the prince as just ruler, the scholar as learned mind, the artist as visionary. The profile becomes a public soul, flattened not to diminish, but to elevate. Yet, the material transformation at the heart of the medallion is as radical as its iconography. Through metallurgic artistry, flesh, fallible, mortal, inevitably fading, is transmuted into something near-eternal. Bronze and silver, once melted and shaped by human hands, become vessels of memory more lasting than the body itself. The very act of casting or striking a likeness declares a belief in continuity: that the self, through art, might escape erosion. In this alchemical operation, the medallist becomes a kind of cultural necromancer, summoning the presence of the absent through touchable, durable form. Circulation magnifies this power. Unlike paintings, which often remain fixed in place, medallions were designed to travel, to be exchanged, displayed, worn, or given. They moved across courts and borders, across centuries and contexts. In their mobility, they became instruments of influence and persuasion, their faces carrying reputations as effectively as letters of introduction or seals of office. A medallion was not simply owned, it was read, handled, revered. It fused the symbolic authority of coinage with the commemorative intimacy of a relic.

Across its long history, the portrait medallion also functioned not merely as a sculpted likeness but as a codex of fashion. Hairstyles, jewelry, drapery, and insignia were more than ornament; they were signifiers of cultural values, dynastic legitimacy, and shifting conceptions of identity. In bronze, silver, or gilt, these fashions were fixed in permanence, transforming transient trends into enduring symbols of an age. Fashion on medals thus reveals the zeitgeist of each era: the sober classicism of Renaissance courts, the theatrical grandeur of the Baroque, the neoclassical austerity of Napoleonic France. These small disks, often overlooked, offer profound insight into the visual culture of their time, reminding us that in every curl of hair or fold of drapery lies not only a sitter’s likeness but an entire cultural moment, cast into metal for posterity.

Thus, each medallion is also a kind of monument: compressed, portable, and profound. It condenses narrative, virtue, and presence into a hand-held sculpture, no less solemn for its scale. While modern viewers may encounter these works behind glass, their original potency lay in their tactility: they were designed to be touched, turned, and contemplated. They operated as miniature tombs of ambition, each one preserving a carefully curated self against the entropy of time. In the final measure, the Renaissance and Baroque medallions examined here do more than reflect an era’s taste for classical revival or humanist image-making. They reveal how art, when shaped into the most enduring of materials, could become a ritual of remembrance. Through bronze and silver, identity was not merely shown, it was cast, struck, and set forth into the world to endure. Today, these medallions return our gaze not only as artworks, but as powerful metal mnemonics: monuments of memory in miniature, where failing flesh has been translated, immortally, into form.

A Philosophy of Permanence

“The medallist becomes a kind of cultural necromancer.”

The Mnemonic Sigil Perdures: Italian Renaissance and Later Metal Medallion Portraits from the Frick Museum Collection O’Connell (2025)

Ultimately, what makes the Renaissance portrait medallion so enduring is its philosophical audacity. It suggests that the self can be rendered eternal. That a life, reduced to profile and phrase, might resist oblivion. That metal, malleable yet immutable, can transmute mortal likeness into myth.

In an age saturated with fleeting images and digital ephemera, the medallion offers a different proposition: memory made material. A face made lasting. A legacy held in the palm of your hand.

Visiting the Frick

If you find yourself in New York City, take time to step into the Medals Room at The Frick Collection. It’s a space of quiet radiance, where history isn’t painted on walls, but held in cases. There, amid the gleam of bronze and silver, you’ll see not just faces from the past, but an entire theory of portraiture cast in metal.

A theory that still speaks, centuries later.

Dr. Mark Joseph O’Connell

This article is adapted from the original scholarly essay, “The Mnemonic Sigil Perdures: Italian Renaissance and Later Metal Medallion Portraits from the Frick Museum Collection”, which offers a deeper academic exploration of the subject. You can access the full article here:

Reference List

Alston, Richard. 2002. Aspects of Roman History AD 14–117. London: Routledge.

Attwood, Philip. 2015. “Giovanni Bernardi and the Question of Medal Attributions in Sixteenth-Century Italy.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 165–176. New York: Routledge.

Chandler, David. (1973) [1966]. Napoleon. New York: Saturday Review Press.

Clain‑Stefanelli, Elvira. n.d. “A Brief History of the Medal.” American Medallic Sculpture Association. Accessed August 2025. https://amsamedals.org/a-brief-history-of-the-medal/#:~:text=Man’s%20quest%20for%20immortality%2C%20his,preoccupations%2C%20fears%2C%20and%20hopes.

Cunnally, John. 2015. In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 115–136. New York: Routledge. “Changing Patterns of Antiquarianism in the Imagery of the Italian Renaissance Medal.”

Doyle, William. 2018. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fichtner, Paula Sutter. 2014. The Habsburgs: Dynasty, Culture and Politics. London: Reaktion Books.

Fitzwilliam Museum. n.d. “Medal of Francis I King of France.” Accessed August 2025. https://fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/explore-our-collection/highlights/CM36-1967.

Frick Museum. n.d. “Renovation and Enhancement Project: 2021–2025.” https://www.frick.org/renovation.

Gosman, Martin, Alasdair James Macdonald and Arie Johan Vanderjagt. 2005. Princes and Princely Culture: 1450–1660, Leiden & Boston: Brill,

Hall, Sierra. 2021. “‘On account of high merits’: The portrait medals of Isabella d’Este and the image of the female collector.” PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,

Jones, Mark. 2015. “Correct and Incorrect: The Composition of Medallic Reverses in Late Seventeenth-Century France.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 221–236. New York: Routledge.

Lippincott, Kristen. 2015. “‘Un Gran Pelago’: The Impresa and the Medal Reverse in Fifteenth-Century Italy.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 75–96. New York: Routledge.

Maué, Hermann. 2015. “Classical Subjects on Erzgebirge Medals.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 201–220. New York: Routledge.

Met. 2016. “Portrait Medals: History and Production Processes.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 2025. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2016/renaissance-portrait-medals/exhibition-themes.

Met. n.d. “Medal: John VIII Palaeologus.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 2025. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/460849.

Met. n.d.-b. “Medal: Francesco II Gonzaga.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 2025. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/461144.

Met. n.d.-c. “Model for a Portrait Medal of Francesco Redi.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 2025. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/461152.

Met. n.d.-d. “Francesco Redi.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 2025. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/207550.

Ng, Aimee. 2016. “Portrait Medals from the Scher Collection Come to the Frick.” The Frick Collection, July 25, 2016. https://www.frick.org/blogs/curatorial/portrait_medals_scher_collection.

Palmer, Alan. 1994. Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

Pollard, J. Graham. 2015. “Text and Image.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 149–164. New York: Routledge.

de Rémusat, Madame. 2023. Memoirs of the Empress Josephine: The Life of Josephine Bonaparte and the Story of the Rise of Napoleon. Good Press.

Scher, Stephen K. 2015. “An Introduction to the Renaissance Portrait Medal.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 1–26. New York: Routledge.

Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. 2015. “A Creative Moment: Thoughts on the Genesis of the German Portrait Medal.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 177–200. New York: Routledge.

Stahl, Alan M. 2015. “Mint and Medal in the Renaissance.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 137–148. New York: Routledge.

Waddington, Raymond B. 2015. “Pisanello’s Paragoni.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 27–46. New York: Routledge.

Waldman, Louis Alexander. 2015. “‘The Modern Lysippus’: A Roman Quattrocento Medalist in Context.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 97–114. New York: Routledge.

Woods-Marsden, Joanna. 2015. “Visual Constructions of the Art of War: Images for Machiavelli’s Prince.” In Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal, edited by Stephen K. Scher, 47–74. New York: Routledge.

Dr. Mark Joseph O’Connell